Below is an excerpt from the book Hi Friend by Jess Hilliard (his Substack is also highly recommended).

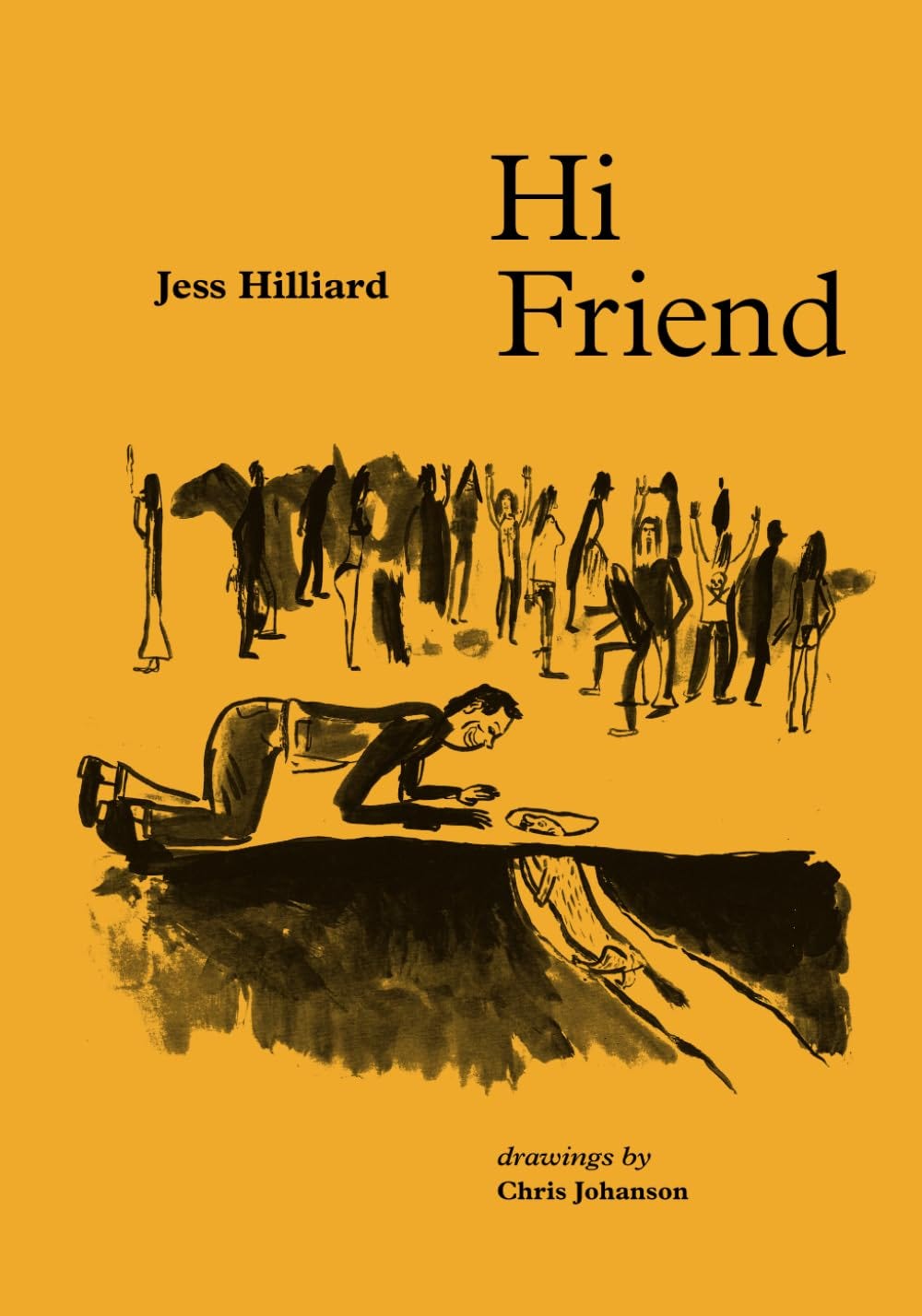

The content, written on scraps of paper in the early 1990s, describes Jess’ experiences and thoughts during a couple of years of being transient. It was first published as a small edition book in 2000 by Tender Feeling Press, and was just reissued by Some People Press. The book has incredible illustrations by Chris Johanson throughout. In many ways Hi Friend was the model for the Some People Press project, and the idea that untrained writers can create amazing books, if given the opportunity.

…………

Well, every person in Texas that I am in the family of was at my grandparents’ house in Honey Grove, Texas. My mom and I were some of the first there. My grandpa is kind of insane, and so is my grandma—she thinks everything is beautiful and lovely and that the family she raised had a close, loving, easy life. All the kids know things were real tough, but her mind makes everything neat and pretty. Well, Pawpa calls me J.P. His name is Parks, his first name, and I’m named after him, so he’s real proud of that. “J.P, I don’t call you Jesse ʻcause your name is Parks, the only two Parks in the family—there, did I hurt yer hand?” He squeezes my hand real hard in a “real handshake.” I squeeze back just as hard, which makes it hurt even more, but I know he feels it too. “Nu-uh.” I tell him. “You know why I shake so hard? ʻCause I’m a Texan, and that handshake says I’m a TEXAS man.” “Parks!” Grannie scolds from the kitchen. “You know whose truck that is out there?” he asks me. “Yeah, it’s yours.” I say. “I always been a Dodge man,” he tells me. Then he takes me out and lifts the hood. “There’s enough room in there for me to stand inside to work on it. It’s a powerful engine, I’m a powerful man, always been, for 72 years I been a powerful man. But these days I’m powerful for about five minutes, then it’s time to feed the dogs.” He’s way over six feet tall & weighs 240 pounds, he’s not really fat, he’s big and he’s powerful, and crazy, but he’s got humor, I think.

“My get up and go, got up and went,” he says referring to his five minutes of power. “Let me show you the dogs.” He built their kennels, “the middle forty” he calls it, and he built everything there, the porch, the trailer, the garden (which feeds both of them all year round), and he built the corral that he keeps his truck in. “These dogs ʻn kill anything. They won’t eat it, but they’ll kill it right away.”

Over the years my grandfather has had many dogs. They grow old and die, or kill each other, but he always replaces them with duplicates which he gives the same names as the ones before them. But then both Pawpa & Grannie act like the dogs are the same ones they’ve always had, even though we all know different. He always has one real mean dog called Fritz. “Fritz come here!” he yelled, and this dog bounded over to him. He grabbed his muzzle, shook it around and stuck his finger in its mouth and shook the dog’s face as it growled. “This dog is half shepherd & half Pitbull,” he said. “That there is Junior.” Junior was an entirely different looking dog. “You mean it’s father and son?” I ask. “That’s right, if you step in there, they’ll kill ya.” But then a few minutes later he told me it was safe to put my hand over and pet ʻem. “They’ll git me!” “Nahhhh, they won’t get you, why, the other night I heard ʻem barking and growling and carrying on, so I came out to see what was going on, I looked up and saw the silhouette of a cat up there on the roof, well he got scared and just jumped down here, and they killed him, about two seconds and that cat was flat as a pancake. They didn’t eat him, just killed him. Well, they ate his tail.”

Then we talked some more, and I heard Grannie away back by the house calling the dogs, these ones and the two others, over for their coffee. “They fight over their coffee, if we don’t give ʻem their coffee they carry on and fight, and oh they love their coffee. Why a few days back a big ol’ rooster got in there, and I mean he was big, well he didn’t last two seconds—they didn’t eat him, just killed him.” He laughed a little and looked around, “That ol’ rooster” he said on the breath of the last bit of his chuckle. “Yeah boy, I tell ya—uh armuhdiluh got in there one time.” “Did they eat him?” “Well, you bet...” he said, “they ate his tail...that ol’ thing just started diggin’ and diggin’, but he hit a root (he pronounced it “rut”) and he couldn’t go no further...” “Oh no!” I said.

Then we went inside to eat. I don’t know, a bunch of stuff happened, we opened some presents and ate some food, and after a while we all started talking about music. As it turned out we all play the guitar & the bass. I didn’t have my guitar with me, but two of the kids had their basses out in their cars, so they went out and got them. Then Pawpa pointed to either side of his easy chair. There was a guitar case propped up on one side of it and a bass case propped up on the other side. With those cases standing up on both sides the easy chair looked like a throne. He said, “I’m not a fan of Elvis Presley, but I got a guitar like him.” And he showed us. Then he put it away and got out his bass and plugged it into his amp, which is two hundred watts, he told us. He has some tapes that he plays with, like Hank Williams and stuff like that. He has a fiddle too, but when I asked him about it, he said that Grannie doesn’t like it when he plays music. And she doesn’t—she always comes right in and tells him not to play anymore.

“I just saw on that violin anyways,” he said. “But used to be, I’d play on that thing and make your Grannie cry...she’d say, Parks, why do you play that thing so sad?” Then he started to laugh a crazy laugh that sounded like a hyperventilating wheeze, and he pushed play on his tape. All four speakers started playing that twangy, upbeat county and western music, and he played along with it. It was hard to hear him play, but you could feel it—he closed his eyes and shut his mouth and stood up on the chair and turned slowly to and fro as he played the bass. He made some mistakes, but it was hard to tell, ʻcause he played fast.

It was hard to tell what he was doing; he could’ve been playin’ anything. And he wouldn’t stop, song after song, maybe sometimes he’d say, with his head turning slowly and his eyes and mouth closed, “mmm, little bluebird...” But I think I was the only one who heard him because he barely said it. He played until people just started leaving, ʻcause at first it was like he was showing us something, but after a half hour or so with his eyes closed nobody knew what to do. We were getting kind of tired, and it was hot in that little trailer, and smoky, and hard to breathe because the fireplace was going with lots of wood in it, and it wasn’t even cold outside. Smoke was coming in the room from the fireplace. I couldn’t stop coughing after a while and I felt bad.

The presents were opened, and everybody got this or that. Paper was everywhere, little kids were playing with their silly putty and dolls, but all the grown-ups got the same little rectangular package from Pawpa—a cassette tape, with nothing written on it. At first, I thought I was the only one who got a tape, but after a while I realized that we all had one. When everyone started to leave and the reunion and everything was over, Pawpa started telling everybody (actually I heard him say this about five times) “Oh, Honey...” he calls everybody Honey, well, he calls me Parks, or J.P, well anyway, “Oh, Honey, you know I made the same tape for everybody. I made one master, but I was preachin’ to y’all. I went out and had each one a-you in mind...” And then (again) I think I was the only one to hear him as he whispered to himself, he wasn’t looking at anyone or anything, he just kinda said it to himself. We were all standing around hugging each other saying goodbye, I was right there beside him in the kitchen, he said, “I really got the feeling of the Holy Ghost.”