An excerpt from The Blacksmith

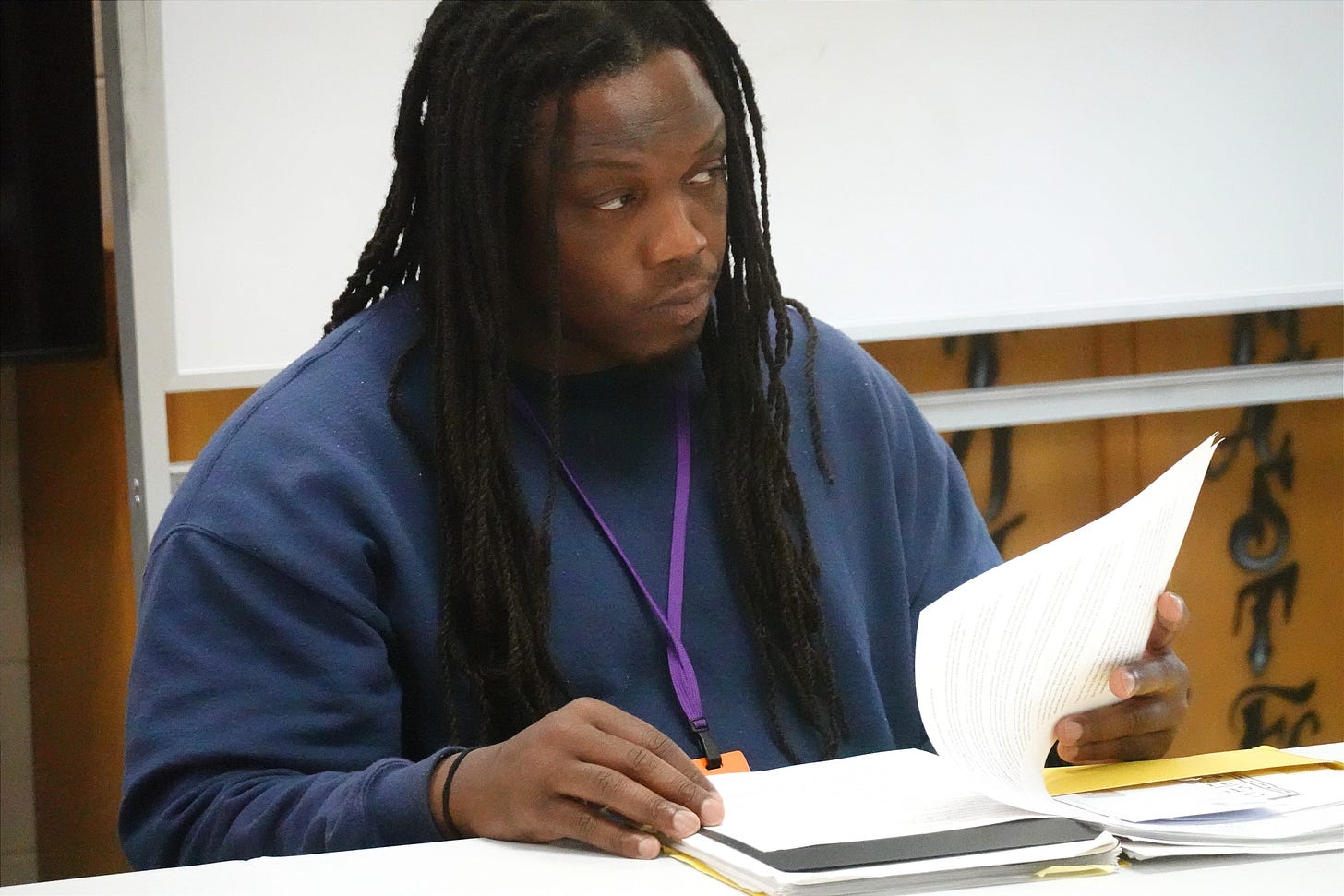

This is a story from Juliano Miller's soon to be released autobiography, The Blacksmith.

Juliano worked solidly for over a year to produce the content for his book. He was always a positive force in the prison writing workshop, consistently bringing in strong writing and encouraging others. Since his release we have met up several times to edit his writing for publication.

…………………

When I was twelve or thirteen my mom caught me with about a queez (a quarter ounce of crack). I thought I’d stashed it in a safe place, under my bedroom carpet, a move I’d seen her do, but she obviously knew that one. She woke me up by slappin’ me in the head, “Boy, wake yo’ ass up. You wanna sell dope?”

I was in my boxers with no shirt, half asleep and trying to think of a lie, but I couldn’t. She said to come downstairs and show her how to bag it. I walked downstairs to the kitchen, pulled a couple of sandwich bags out of the box, grabbed a plate and a razor, and did my thang.

My mom said, “Boy, you did that like a professional. I should beat yo’ ass,” with a half smirk on her face.

I was spooked, but also proud of my baggin’ skills. I still remember the feeling, like I’d accomplished something major, like provin’ somethin’ to a big brother or sister that they never thought you could do.

Then she said, “Go outside and sell it.”

“Mom, I’m tired.”

“Shut the fuck up and do what I said.”

I headed toward the stairs to go to my room and get somethin’ warm to put on and my shoes, but she said, “Uh uh, those is my clothes.”

“It’s cold outside.”

“You should’ve thought about that before you brought drugs in my house. Now hurry up and show me how you do it.”

I started to complain, but before I could say another word, she swung on me. I said, “OK, OK” with fear in my voice. I opened the front door and went outside. All the dope was bagged up on the white plate I’d cut it on. I held it in my hands as I headed to the sidewalk, looking down the block to see if there was any clucks out there.

My mom grabbed a chair and set it in front of the door, sat down, and watched me as she lit up a cigarette. After about ten or fifteen minutes, which felt like an hour out there in just my boxers, I said, “Ain’t nobody out here right now.”

“Don’t come in this house till it’s all gone.”

I smacked my lips and turned around again. After about five more minutes, I said, “I ain’t doin’ this no more.”

“What you say?”

I said, “I ain’t doin’ this no more,” and flipped the white plate in the air, sending the dope flyin’ into the middle of the street. The plate broke on the ground. I was thinkin’, “I’m just gone take my ass whoopin’ so I can go in the house and go to sleep.”

My mom said, “Get yo’ ass in the house,” and I hurried up, leaving the crack where it was, and the dope game behind for the night.

“I don’t ever wanna catch you sellin’ or bringin’ dope into my house again.”

“OK, I’m sorry.”

“I love you. Go to bed, you got school in the morning.”

In the world of boxing, she won that round, but when I was thirteen or fourteen, she had a bigger fight on her hands: cancer. I watched her go from being vibrant and social, to barely comin’ outside, to losin’ her hair and wearing handkerchiefs on her head on the daily. I tried to step up, cook, wash dishes and clothes, keep the house clean, and get her outside for air. It was a crazy experience, but I didn’t have time to be sad or cry over it. I had to be strong for both of us.