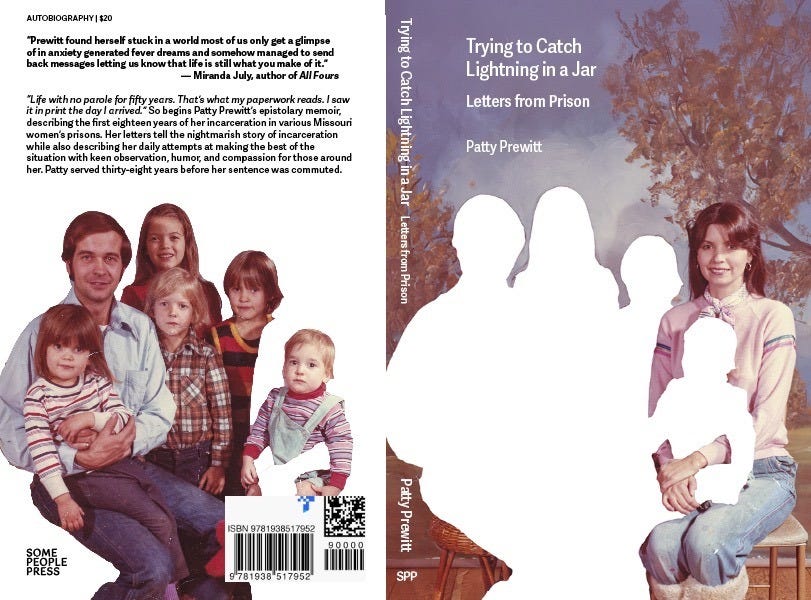

Now available for purchase: Trying to Catch Lightning in a Jar

…….

“Prewitt found herself stuck in a world most of us only get a glimpse of in anxious fever dreams and somehow managed to send back messages letting us know that life is still what you make of it.”

December 16th, 1989

Dear Mary,

I’m back at Renz, where I started my prison career. Don’t know where to begin. This has been a nightmare inside a nightmare.

At Chillicothe, while guards wound chains around us in preparation for our before-dawn trip, the friends we left behind hugged us and cried farewell. Once we were loaded on the bus, everyone settled in for a silent but tense ride. As the bus neared Jefferson City, nervous chatter began.

Helen sat next to me, wrung her hands as best she could in handcuffs, and fretted. Those of us who had been at Renz before were well aware of how horrid it would be. The newer girls had not a clue—which made their trip easier.

When Helen and I caught sight of the old prison, big tears welled up in her sad eyes. It was true. We were on our way to be redeposited in Hell.

Unloading, unshackling, unchaining, finding our property, sorting through it all with staff, and carrying the boxes up the concrete steps to the top floor was mayhem. I can’t begin to describe the disorganization. None of the staff knew what to do or how to do it.

When we finally made our way up to the dorm, and as our friends, who had arrived two days before, were hugging us in welcome, we looked over their shoulders in disbelief. The windowpanes are cracked—some broken clear out. Ice is frozen on both sides of the remaining glass. The snow blows in. I’m not kidding. Needless to say, it’s chilly in here.

Dingy, stain-streaked state sheets have pathetically been stapled to most of the tall windows in a feeble attempt to keep the howling north wind at bay. They blow in and bulge and flap like sails, as if we are lost at sea. Some of the girls say that in the middle of the night, the sheets look to them like gray ghosts straining to enter—and the eerie moan of the wind only adds to the illusion.

But the cold is not the worst part. The filth is. Nicotine is so thick on the walls that the cracked concrete looks like it was painted with thick brushfuls of walnut stain—and the stain ran. The small, rusted metal tables provided for each cubicle are covered on one side or the other with a thick stubborn layer of crud made out of dust, straw, cobwebs, and manure that formed when the furniture was stacked and stored in the barn—since the War Between the States, I think. The hollow, rusted-iron bunk bed posts are completely full of cigarette butts. I refuse to describe the showers and toilets since you might be eating supper while reading this. Men, nasty men, have had this prison for three years, and it shows.

The odor. Lord, the strong odor of men’s urine and stale sweat plus old tobacco plus other indescribable stench permeates the air. How can it stink so badly with so much ventilation? One of the girls keeps a bandana tied around her nose like an old-time bank robber. In defense, she rubbed the scarf with a magazine perfume sample. Good idea.

Our chairs are upside-down, empty, plastic pickle buckets. As I sit and scribble this, a permanent and perfect circle is embedding itself in my butt.

And I didn’t even see the mess in all its glory. The first wave of women had been cleaning for two days before we arrived. Unbelievable.

Because there are still male inmates housed in this camp, we’re on lockdown status—and don’t know how long that will be. Platt Junior College has a paralegal class here and offered me a job, so I’ll be back at work soon.

At CCC we lived in cells for the most part: two or four-woman rooms. But Renz Farm’s housing is open bays. Rows of rusted iron bunk beds in big open rooms. No privacy. Burning up in the summer; frigid in the winter. At least with the cold, the roaches aren’t so troublesome.

I’ve never seen my compadres look so worn. They’re sporting dark circles under their haunted eyes from the strain. We resemble raccoons who suffer from severe insomnia. No one is sleeping well. We’re cold, crowded, and crazed.

Many of the guards have never worked with females and don’t seem to want to. They are mean and rude—can’t understand why we demand mops and cleaning supplies. Some of the old guards remember and have warmly welcomed us. They look forward to a cleaner, sweeter smelling, “kinder, gentler” work environment.

My theory is that the-powers-that-be want the legislature to appropriate funds to build a new women’s prison, and we’re pawns in the plan. If we holler about the abhorrent conditions, maybe they’ll get the money.

Meanwhile, we will clean this place up and try to make the best of a bad situation. That’s what we do best.